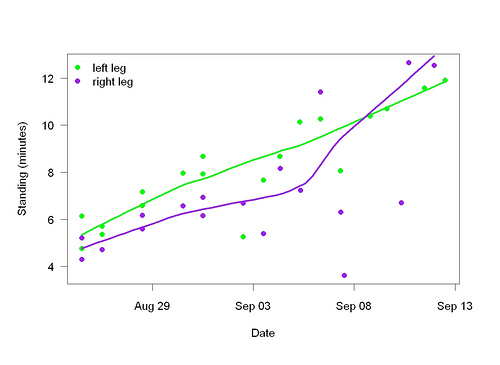

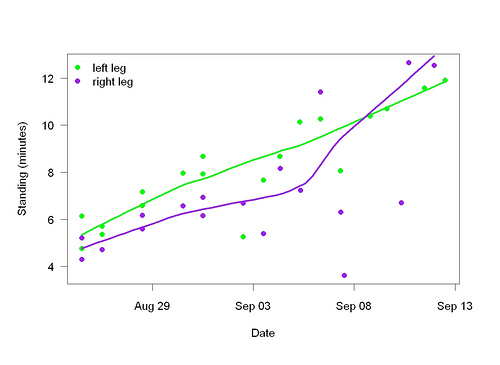

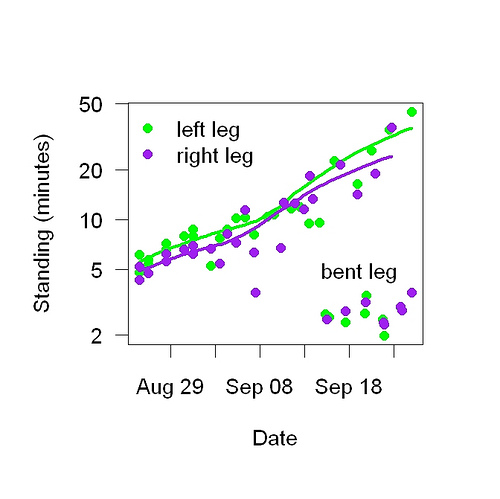

When I talk about how standing on one leg has helped me sleep better, the inevitable question is how much standing? After I became sure the standing was making a difference, I started to record the durations. I always stood on one leg until it became a little hard to continue. As my legs have become stronger, this has taken more time, as this graph shows:

During the early days on this graph, I didn’t include time-of-day information. I usually stood on one leg three or four times per day. More recently, I have included time-of-day info and now stand on one leg only twice most days. In all of the cases shown on the graph, I was pulling my other leg back behind me at the same time, stretching the muscles. (If I don’t stretch the other leg, I can stand one-legged much longer.) In the very beginning, I only stood one-legged 2-3 minutes.

I’m sleeping better than any other period in my adult life. My sleep was pretty good before this period but the difference is still huge. Not only am I sleeping better, I suspect I’m also sleeping less (as happened when I improved my sleep by standing a lot).

I suppose one-legged standing counts as “exercise” — that source of so many claimed benefits (longevity, weight loss, less heart disease, etc.). I read today that exercise is supposed to improve your brain. But the differences between what I am doing and what is usually recommended are as large as the difference between the Shangri-La Diet and other diets:

1. Conventional exercise: Requires expanse (for walking) or, usually, special equipment (e.g., gym). Takes one hour or more, when you count changing clothes and showering, not to mention the drive to and from the gym. One-legged standing: Can do almost anywhere. Takes less than 30 minutes, so far.

2. Conventional exercise: Requires discipline if you want a decent workout in a reasonable amount of time. One-legged standing: Almost no pain involved. I can watch TV or read something at the same time.

3. Conventional exercise: Supposed to be aerobic if you want the main benefits. One-legged standing: The opposite of aerobic.

3. Conventional exercise: Some benefits accrue slowly, such as weight loss. Others are hard or impossible to detect, such as longer life. Runners’ high goes away, in my experience. One-legged standing: Benefit clear the next morning. Because I am strengthening muscles I use all the time (when I walk or stand) I notice my vastly increased leg strength all the time.

4. Conventional exercise: You want to get stronger. One-legged standing: You don’t want to get too strong or else it may take too long to get the effect.

5. Conventional exercise: Often difficult to measure increased strength. Hard to measure improvement in swimming, racquetball, or aerobics classes, for example. One-legged standing: Easy to measure increased strength.

6. Conventional exercise: Helped me fall asleep faster, but didn’t solve the problem of too-light sleep. One-legged standing: Utterly solves the problem of too-light sleep.

Could the benefits of conventional exercise have anything to do with the fact that it vaguely resembles one-legged standing?

Directory.

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.