At the heart of the Shangri-La Diet is the idea that we learn to associate flavors (smells) with calories. This learning was first shown in rat experiments. There’s some human evidence, but not much. If I could discover more about what controls this learning, I might be able to improve the diet. For example, maybe I could say more about what the flavor-free window should be.

My earlier self-experimentation on this subject – I used tea for flavor and sugar for calories — was helpful. To my surprise, I found that really small changes in flavor made a noticeable difference. If I switched from one canister of Peet’s Gunpowder Tea to a new canister, the ratings went down, although everything else stayed the same. From this came the notion of ditto food: Foods with exactly the same flavor each time are especially fattening. I hadn’t realized what a difference it would make if you kept the flavor exactly the same each time.

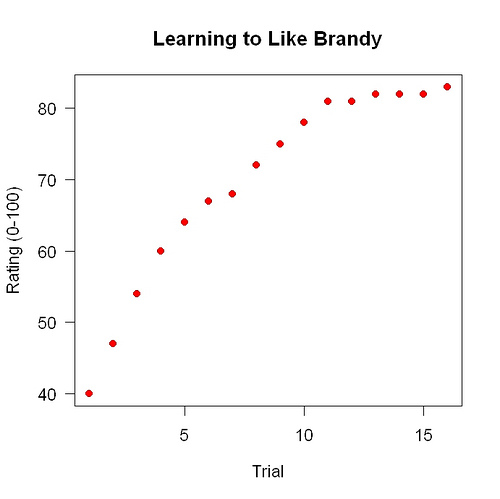

It’s been hard to learn more. After Christmas dinner, my mom gave me the leftover brandy (A. R. Murrow). I used it for a very simple experiment in which I learned to like it. I’ve never drunk brandy in any quantity and I started off not liking it. Every day for a few weeks, I drank one tablespoon. I drank it in a few sips over a few minutes. I didn’t eat anything else for at least 30 minutes. I rated how good it tasted on a 0-100 scale where 10 = very bad, 20= quite bad, 25 = bad, 30 = somewhat bad, 40 = slightly bad, 50 = neutral, 60 = slightly good, 70 = somewhat good, 75 = good, 80 = quite good, 90 = very good. The overall rating was the maximum of the ratings of the several sips. (The first sip usually tasted the best.)

Here are the results.

I’ve observed similar results five or six times. They are more support for the most basic conclusions: 1. The effect is very clear. One tablespoon of brandy has only 30 calories. 2. A really simple experiment is easy.

That’s a promising start but then it gets hard, or at least non-obvious. As a way to study flavor-calorie learning, this little example has several flaws: 1. Slow learning. 2. Expensive materials. 3. Little control of flavor. The best I can do is choose which liquor to buy. Soon I will run out of ones I haven’t used. 4. No way to separate flavor and calories in time. 5. No way to change the calorie source.

An earlier demonstration used a soft drink. It’s really Science in Inaction: I’ve made zero progress in a year.