The success of my self-experimentation has puzzled me. The individual discoveries (a new way to lose weight, a new way to improve mood, sleep-related stuff, the fast effects of omega-3) seem normal; someone would have found them. It’s their combination that’s strange. Scientists who study weight control do not discover anything about mood, for example. But I did.

An ancient (2001) essay by Paul Graham is about how the future lies with web-based applications. No more Microsoft Word. One of Graham’s stories sheds light on my puzzle:

I studied click trails of people taking the test drive [of Graham’s web-based application] and found that at a certain step they would get confused and click on the browser’s Back button. . . . So I added a message at that point, telling users that they were nearly finished, and reminding them not to click on the Back button. , . . The number of people completing the test drive rose immediately from 60% to 90%. . . . Our revenue growth increased by 50%, just from that change.

I studied click trails. He examined a rich data set, looking for hypotheses to test. I practiced what I’ll call spider science: I waited for something to happen. When it did, I started to study it, just as a spider moves to the part of the web with the fly. Here are examples:

1. A change in what I ate for breakfast caused me to wake up early much more often. I did many little experiments to find out why.

2. Watching TV early one morning seemed to have improved my mood the next day. This led to a lot of research to figure out why and how to control the effect.

3. After I started to stand more, my sleep improved. I made many measurements to see if this was cause and effect and if so what the function looked like (the function relating hours of standing to sleep improvement).

4. In Paris I lost my appetite. This started the research that led to the Shangri-La Diet.

5. The morning after I took some omega-3 capsules, my balance improved. This led to experiments to see if it was cause and effect and if so what the function (balance vs. amount of omega-3) looked like.

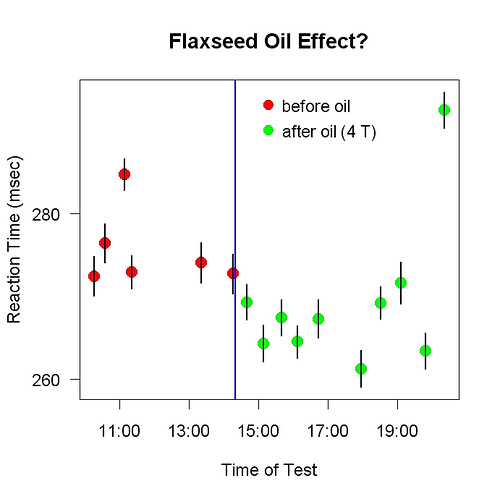

6. One day I took flaxseed oil at an unusual time. My mental scores suddenly improved. I started to study these short-term effects.

7. While studying these short-term effects, I noticed improvements shortly after exercise. I started to study the effect of exercise.

Graham studied click trails partly because he could so easily act on anything he learned, partly because it was his company and he was so committed to its success. The seven examples I have given all came about partly because I could easily act on what I noticed and partly because I would directly benefit from learning more.

Conventional scientists do not practice spider science. They do not continuously monitor or search out large rich data sets hoping to find something they can act on. They can’t afford to, it’s unconventional, it’s too risky, it won’t pay off soon enough, they probably couldn’t act on what they found, etc. Later in Graham’s essay he marvels that big companies develop any software at all. Microsoft is like “a mountain that can walk.” Likewise, I’m impressed that scientists operating under the usual constraints manage to discover anything. You might think tenure allows them to relax, wait, take chances, and do things they weren’t trained to do, but it doesn’t work out that way.