A recent issue of JAMA has an article titled “Comparison of Strategies for Sustaining Weight Loss: The Weight Loss Maintenance Randomized Controlled Trial”. It reports an experiment that compared three ways to keep from regaining weight you’ve lost.

If you want to lose weight it paints a discouraging picture. It was an very expensive study, 27 authors, five grants. About 1000 subjects. Four years just to collect the data. The whole thing might have taken seven years. Must have cost millions of dollars. Might have cost tens of millions of dollars.

Given the huge expense, surely the subjects got the best possible establishment-approved weight loss advice. They did lose 19 pounds in six months. Here’s how the advice was described in the article:

Intervention goals were for participants to reach 180 minutes per week of moderate physical activity (typically walking); reduce caloric intake; adopt the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension dietary pattern . . . and lose approximately 1 to 2 lb per week. Participants were taught to keep food and physical activity self-monitoring records and to calculate caloric intake.

Shades of Marion Nestle’s “move more, eat less”! Aside from the DASH “dietary pattern,” which was meant to reduce blood pressure, not weight, this advice could have been given fifty years ago. Apparently, those who did the study and those who funded it — who are representative of the larger research establishment, I assume — believe there has been no theoretical or empirical progress since then.

Many fields haven’t progressed in 50 years. Fifty years ago, 2 + 2 equaled 4. The basic principles of thermodynamics and inorganic chemistry were the same then as they are now. Lack of progress in weight loss advice would be fine if the advice actually worked but the whole study derived from the fact that the advice is poor — the weight loss it produces cannot be sustained.

To help people sustain their weight loss, the study compared three methods: 1. Monthly contact. Usually a 10-minute phone call (“with an interventionist”), every 4th month a hour face-to-face visit. Although the article claims this treatment was “practical,” I suspect it is too expensive for widespread use. 2. Encouragement to visit an interactive website. The website helped you set goals, allowed you to graph your results, and had a bulletin board, plus several other features. This was the focus of the whole huge research project: the effect of this website. It could be offered to everyone practically free, except that if the subject didn’t log on after email reminders she got a phone call. 3. “A self-directed comparison condition in which participants got minimal intervention [that is, nothing].”

The personal contact condition was slightly better than nothing. By the end of the study, the website was no better than nothing. And nothing was bad. The subjects regained about two-thirds of the lost weight during the maintenance year and, looking at the weight-versus-time graph, were apparently going to regain the rest of the lost weight during the coming year. Subjects in all three conditions continued to regain the lost weight throughout the year of maintenance.

In other words, this exceedingly expensive study could be summed up like this: We tried something new, it didn’t work. The abstract didn’t face this truth squarely. It concluded: “The majority of individuals who successfully completed an initial behavioral weight loss program maintained a weight below their initial level.”

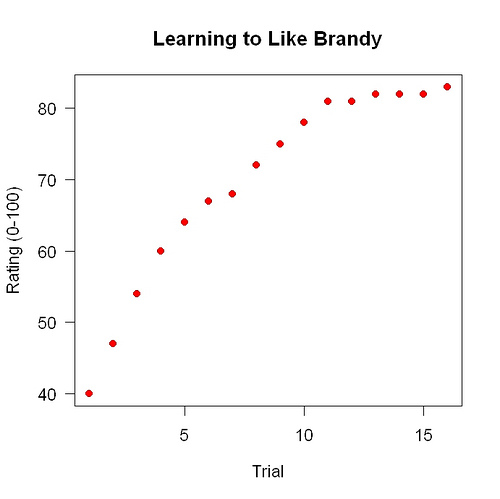

It’s a Catch-22: Without a good theory, it’s hard to find experimental effects. You’re just guessing. Most of what you will try will fail. Without strong experimental effects, it’s hard to build a good theory. I was in this situation with regard to early awakening. I had no idea what the cause was. It took me ten years of trying everything I could think of, dozens of possibilities, before I managed to find something that made a difference. From that I managed to build a little bit of a theory, which helped enormously in finding more experimental effects.

The people who did this study had no good theory about weight control. Nothing wrong with that, we all start off ignorant. The website they tested was just the usual common-sense stuff. What’s discouraging for anyone who wants to lose weight is how little progress was made for such a huge amount of time and money. If it takes seven years and ten million dollars and a small army of researchers to test one little point in a vast space of possibilities . . . you are unlikely to find anything useful during the lifetime of anyone now alive (or any of their children). The people behind the study also had a poor grasp of experimental design. With 300 people in the website group, it would have been easy to test many website design variations: weight-loss graph (yes or no), bulletin board (yes or no), etc., using factorial or fractional factorial designs. Their study merely showed that one particular website didn’t work. They learned nothing about all other possible websites. They might have been able to say: no likely website will work. They can’t because the study was badly designed. The study cost something like $10 million and that was the statistical advice they got!

The huge expense and the lack of progress in the last 50 years go together. The methodological dogmatism I discussed recently has bad consequences. It leads to studies that are more expensive and take longer. The proponents of the methodological rigidity say they are “better” not taking account of the cost: continued ignorance about health. A better research strategy would be to fund and encourage much cheaper ways of testing new ideas.