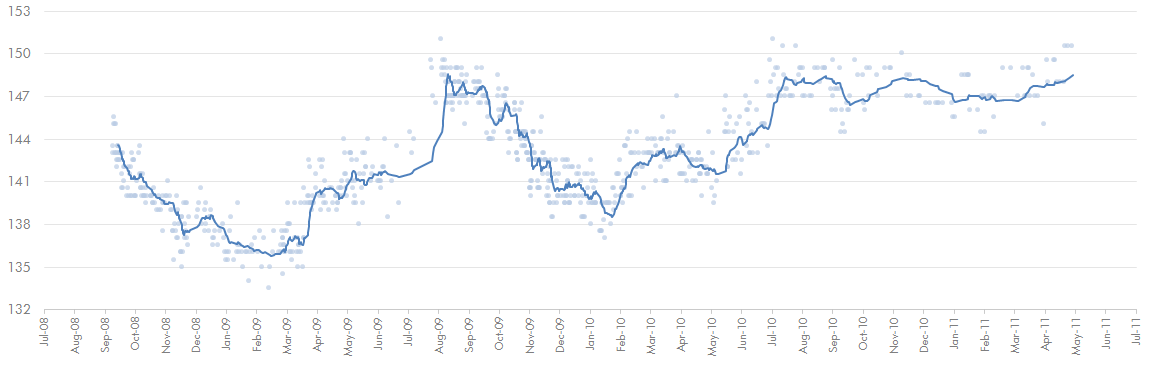

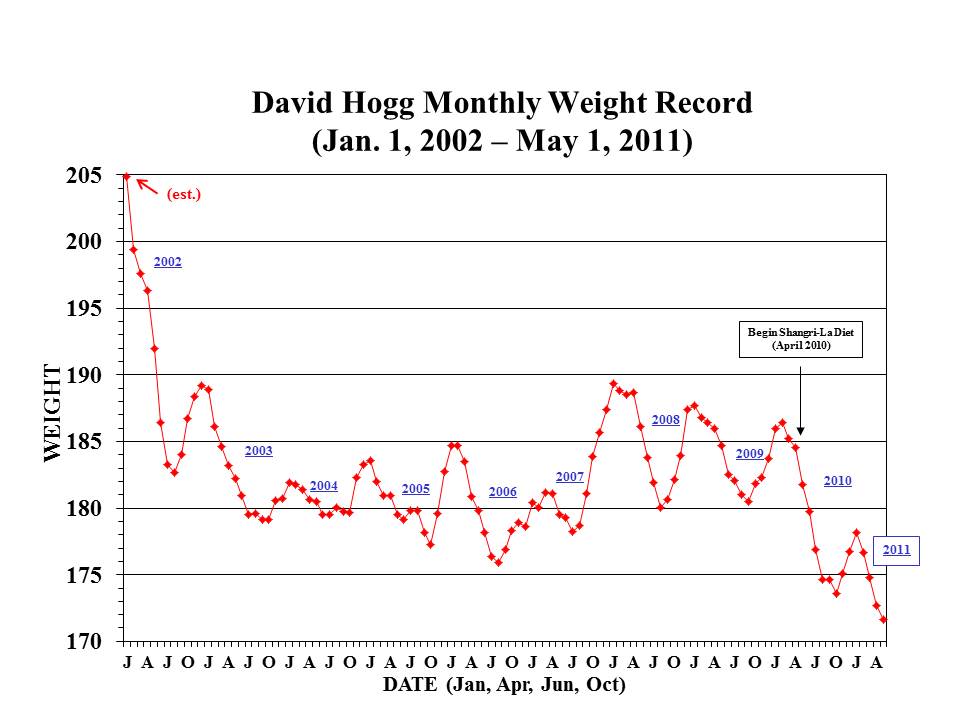

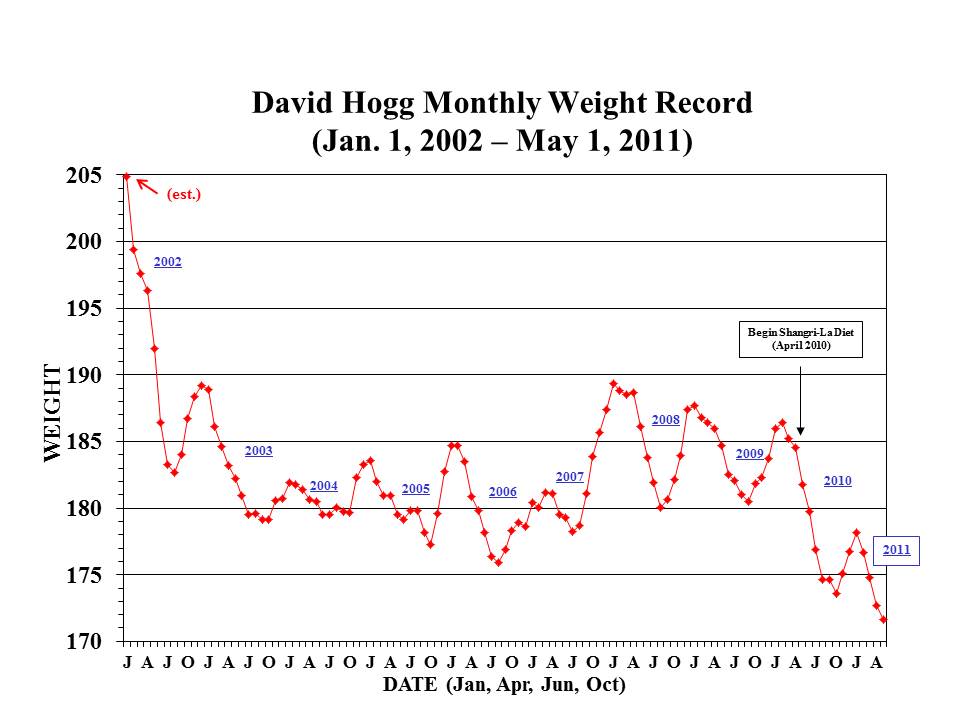

Seeing Alex Chernavsky’s ten years of weights inspired David Hogg, a professor of entomology at the University of Wisconsin, to send me his weight data for the past nine years — see above. Like Alex, he found that the Shangri-La Diet worked where other methods failed.

He is 5′ 10″ and 63 years old. When his weight reached 205 pounds (in 2002) he decided to take serious action. He began by increasing how much exercise he did, to “watch what [he] ate,” and to take “diet” pills. I asked him about the diet pills. He replied:

On [the advice of a local supplement store owner] I began to take L-Carnitine, which has a variety of effects (including some evidence for weight loss?), and an ephedrine based diet supplement (I don’t recall the name of the product). I took the ephedrine until its sale was outlawed (2006?), after which I started taking a NOW Foods product called Diet Support, which lists as major ingredients iodine, chromium, forskolin (from Coleus root), L-Carnitine, extract of Garcinia cambogia, green tea extract, and extract of Uva ursi leaf.

He described “watching what [he] ate” like this:

I started having a fruit smoothy with protein powder and flaxseed oil for breakfast (rather than eggs/cereal and toast) and I cut back from a full sandwich and fruit to a half sandwich and fruit for lunch. I did not modify what I ate for dinner but did attempt to eat less, and I tried to not snack between meals. I think all of this was somewhat successful, although I was hungry a lot and suffered regular setbacks.

He described his exercise like this:

My goal was to get some form of exercise daily. In reality I probably get exercise on average 5 days a week, but this was not too different than what I was doing previously. My primary means of exercise are bicycling and racquetball/squash, but I also golf (walking, not cart) and take a range of classes at a local health club that includes Pilates, spinning, and weight lifting.

In 2002 he increased how much exercise he did.

In 2002, in other words, he began to do conventional weight-loss things (eat right, eat less, and exercise more) plus take diet pills. This lowered his weight from 205 to 180 but not further, even though continued for years. So far the Shangri-La Diet has lowered his weight about 10 pounds. He does it like this:

I started out with sucrose water, after several weeks switched to ELOO (which did not seem to work for me, perhaps because it reminded me of popcorn?), quickly switched to fructose water, which I used exclusively for 6+ months, then switched again to walnut oil (the fructose water made me feel bloated). For the past approximately 4 months I have added fructose to the walnut oil, which I started to use up the large supply of fructose I ordered, but it actually seems to work the best of anything I’ve tried to date. I drink 2 tablespoons of walnut oil containing about a quarter of a tablespoon of fructose, twice daily.

My ideas about dietary control of the set point made a lot of sense to him.

At one time I believed weight gain or loss was purely a matter of calories in vs. calories burned. Up to age 30 that model seemed to explain my weight. After 30 it was not so simple, with my weight seemingly resistant to sustained loss or (in the short term) gain, and this led me to adopt the view that my weight was governed by an equilibrium or set point. This was easy for me conceptually. My professional interest at the time was insect population dynamics, and the prevailing view was that although insect population densities fluctuate (sometimes widely) through time, for a given species the fluctuations tend to occur around an equilibrium that is enforced through density dependent processes. However, I viewed my set point weight as “fixed”, so my paradigm did not explain the upward drift in set point and weight. Your discussion of this, from an evolutionary perspective, made me rethink my idea of a fixed set point and provided the perfect explanation for the upward drift in my weight (plus the way to convince the brain to decrease one’s set point).

His data are an important advance in understanding. They cover a long period of time and allow comparison of the Shangri-La Diet to three popular weight-loss methods: “controlling what you eat”, exercise, and various supplements (“diet pills”). No conventional weight-loss experiment covers as long a period of time.