Last night I slept unusually well, waking up more rested and with more energy than usual. I slept longer than usual: 7.0 hours versus my usual 5.1 hours (median of the previous 20 days). My rating of how rested I felt was 99.2% (that is, 99.2% of fully rested); the median of the previous 20 days is 98.8%. Because the maximum is 100%, this is really a comparison of 0.8% (this morning) with 1.2% (previous mornings); and the comparison is not adjusted for the number of times I stood on one leg to exhaustion, which improves this rating. During the previous 20 days I often stood on one leg to exhaustion six times; yesterday I only did it four times. Above all, I felt more energy in the morning. This was obvious. I have just started to measure this. At 8 am and 9 am, I rate my energy on a 0-100 scale where 50 = neither sluggish nor energetic/energized, 60 = slightly energetic/energized, 70 = somewhat energetic/energized, and 75 = energetic/energized. My ratings this morning were 73 (8 am) and 74 (9 am). The median of my 9 previous ratings is 62. The energy improvement (73/74 vs 62) is why I am curious. I would like to feel this way every morning.

What caused it? I had not exercised the previous day. My room was no darker than usual. My flaxseed oil intake was no different than usual. I had not eaten more pork fat than usual. However, four things had been different than usual:

1. 2 tablespoons of butter at lunch. In addition to my usual 4 tablespoons per day.

2. 0.5-1 tablespoons of butter at bedtime. Again, in addition the usual 4.

3. 1 tablespoon (15 g) coconut butter at bedtime. Part of a longer study of the effect of coconut butter. Gary Taubes suggested this. I had eaten 1 T coconut butter at bedtime 13 previous days. On the first of those 13 days, I had felt a lot more energetic than usual in the morning. On the remaining days, however, the improvement was less clear. I started measuring how energetic I felt in the morning to study this further. Last night was Friday night. On the previous two nights (Wednesday and Thursday) I had not eaten the coconut butter. Maybe absence of coconut butter followed by resumption of coconut butter is the cause.

4. Fresh air and ambient noise. Following a friend’s suggestion, I opened one of my bedroom windows.

My first question is whether the improvement is repeatable. If so, I will start to vary these four factors.

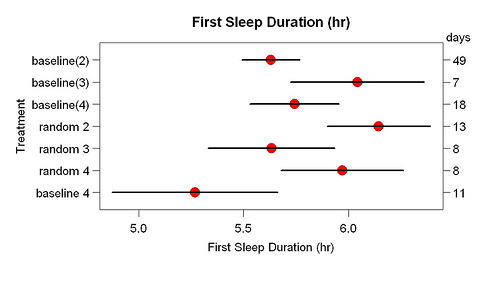

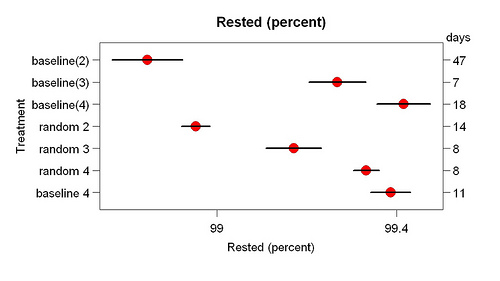

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.

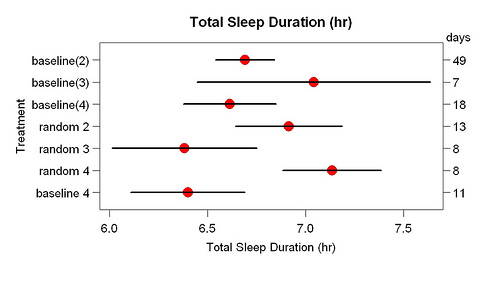

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.