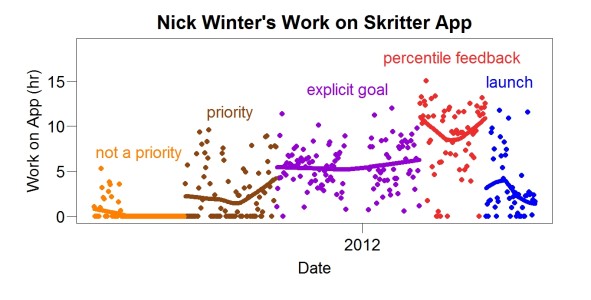

How much did percentile feedback help Nick Winter? In 2011, he wanted to finish coding a mobile app for Skritter. This graph shows his daily work on that app. Each point is a different day. The lines are loess fits.

At first, he tried to work on the app but did not make it a priority. Then he made it a priority compared to other things he did. Then he set an explicit goal (a certain number of hours of work each day) and used Beeminder to help reach that goal.

Finally he tried percentile feedback. It helped a lot. His work per day increased about 60% (to 8.6 hours/day) compared to the previous phase (5.5 hours/day). Using percentile feedback, he finished the app. During the launch, he worked on the app much less.

The data has several interesting features. One is the sudden improvement when percentile feedback started. The same thing happened to me. Another is that it helped him even though he was already making steady progress. A third is that the sudden improvement happened after he had been working on the task a long time (more than six months). Things become easier to do the more we do them but surely this change was complete by the time he started percentile feedback. Apparently it engaged a different source of motivation. Finally, he tried several things before he tried percentile feedback, implying that its value wasn’t obvious. It wasn’t obvious to me, either. I originally tried it to see what would happen. I didn’t have a strong belief it would work.

Above all, this graph shows it’s possible to learn from long-term self-measurement and what you learn may not be obvious. People who know little about research sometimes say that randomized double-blind trials are the only convincing way to learn something.