One of my students grew up and went to high school in Nanjing, population 8 million. Her acceptance to Tsinghua was such a big deal that when her acceptance letter reached the local post office they called to tell her. The post office also alerted journalists. When the letter was delivered to her house, there were about 20 journalists on hand. One of them, from a TV station, asked her to say something to those who failed.

Thirty Years of Breast Cancer Screening May Have Done More Harm Than Good

A recent op-ed in the New York Times by H. Gilbert Welch, a co-author of Overdiagnosis, describes a tragedy of ignorance and overconfidence. The current emphasis on regular mammograms began thirty years ago. They will prevent breast cancer, doctors and health experts told hundreds of millions of women. They will allow early detection of cancers that, if not caught early, would become life-threatening. The campaign was very successful. According to the paper cited by Welch, about 70% of American women report getting such screening.

It is now abundantly clear this was a mistake. If screening worked perfectly — if all of the cancers it detected were dangerous — the rate of late-stage breast cancer should have gone down by the amount that the rate of early-stage breast cancer went up. Over the thirty years of screening, the rate of (detected) early-stage breast cancers among women over 40 doubled, no doubt because of screening. (Over the same period the rate of early-stage breast cancers among women under 40 barely changed.) In spite of all this early detection and treatment, the rate of late-stage breast cancer among women over 40 stayed essentially the same. All that screening (billions of mammograms), all that chemo and surgery and radiation, all that worry and time and misery — and no clear benefit to the women screened and those who paid for the screening, treatment, and so on. Roughly all of the “cancers” detected by screening and then, at great cost, removed, aren’t dangerous, it turns out.

Quite apart from the staggering size of the mistake and the long time needed to notice it, screening has been promoted with specious logic.

Proponents have used the most misleading screening statistic there is: survival rates. A recent Komen Foundation campaign typifies the approach: “Early detection saves lives. The five-year survival rate for breast cancer when caught early is 98 percent. When it’s not? It decreases to 23 percent.” Survival rates always go up with early diagnosis: people who get a diagnosis earlier in life will live longer with their diagnosis, even if it doesn’t change their time of death by one iota.

Did those making the 98% vs. 23% argument not understand this?

I applaud Welch’s research, but his op-ed has gaps. A unbiased assessment of breast cancer screening would include not only the (lack of) benefits but also the (full) costs. Treatment for a harmless “cancer” may cause worse health than no treatment. Maybe chemotherapy and radiation and surgery increase other cancers, for example. What about the effect of all those mammograms on overall cancer rate? Welch fails to consider this.

Welch also fails to make the most basic and important point of all. To reduce breast cancer, it would be a good idea to learn what environmental factors cause it. (For example, maybe poor sleep causes breast cancer.) Then it could be actually prevented. Much more cheaply and effectively. Yet the Komen Foundation and the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation say “race for the cure” instead of trying to improve prevention.

Assorted Links

- Has the impact of Helicobacter pylori therapy on ulcer recurrence in the United States been overstated? “20% of patients in these studies had ulcer recurrence within 6 months.”

- Over-sold flu vaccine. Carl Zimmer in the NY Times, however, says “The vaccines usually provide strong protection against the virus.”

- Incredibly fast mental addition.

Thanks to Paul Nash, Grace Liu and Anne Weiss.

The Physical Spacing Effect: New Way to Learn Chinese Works Shockingly Well

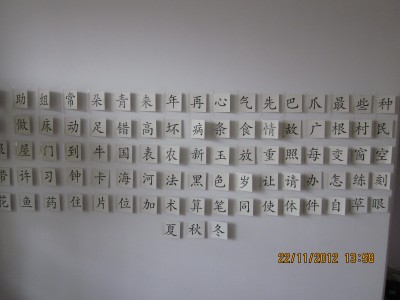

Two years ago I taped a bunch of Chinese flash cards (Chinese character on one side, English meaning on the other) to my living room wall (shown above). I’ll study them in off moments, I thought. I didn’t. It was embarrassing when guests pointed to a card and said, “What’s that?” But not embarrassing enough.

A few weeks ago, I can’t remember why, I decided to test myself: how many do I know? About 20%. I’ll try to learn more, I thought. I was astonished how fast I learned the rest. It took little time and almost no effort. I didn’t need “study sessions”. I glanced at the array now and then, looked for cards I didn’t know yet, and flipped them to find out the answer. After a few days I knew all of them.

I had been using conventional methods (flash cards studied in ordinary ways, Anki, Skritter) and an unconventional method (treadmill study) to learn this material for years. In spite of spending more than a hundred hours on each method, I had never gotten very far. I might get to 500 characters and backslide due to lack of study. Treadmill walking while studying made studying much more pleasant, but I found I would still prefer to watch TV rather than study Chinese. Maybe part of the problem was too many days skipped. After you skip four days, for example, you have a discouragingly large number of cards to review. Plainly these methods work for others. They didn’t work for me.

After my success with the two-year-old cards, I put up another array (8 x 13). I already knew about 40% of them. I learned the rest in a day or so. Then I put up a 10 x 12 array. I tested myself on them one morning. I knew 30 of them. I studied them during the day for maybe 30 minutes in little pieces throughout the day. The next morning I tested myself again (about 12 hours from the last time I had studied them). Now I knew 105 — I had learned 75 in one day, almost effortlessly. That day I studied for a few minutes. The next morning I tested myself again. Now I knew all but one of them.

I did not notice any facilitation of learning when I studied flash cards while walking around. In that case, unlike this one, (a) they were in roughly the same position relative to my body and (b) had no consistent physical location. I noticed the same facilitation of learning during a Chinese lesson in a cafe. I was having trouble remembering three Chinese words (e.g., the Chinese word that means graduate). I wrote each of them on a piece of paper with the English on one side and the Chinese on the other. I put the three pieces of paper at widely-separated places on the table. I studied them briefly, a few seconds each. That was enough. Five days later I still remember them (having used them a few times since then). This happened in a place (a cafe) with which I wasn’t familiar, unlike my living room. Maybe the general principle will be it is much easier to learn an association if it is in a new place.

It’s very early in my use of this method, but I doubt it’s a fluke. It connects with several things we (= psychology professors) already know. 1. The mnemonic device called the method of loci. You put things you want to learn in different places in a well-remembered landscape (e.g. different places in a building you know well). Usually the method is used to learn lists, such as the digits of pi or the order of cards in a deck. You place different items in the list in different places in the imagined place. Then you “walk” (in your imagination) through the imagined place. The method dates back to ancient Rome. 2. The power of interference. Thousands of experiments have shown that learning X makes it harder to learn similar Y. X and Y might be two lists, for example. The greater the similarity, the bigger the effect. What you learn on Monday makes it harder to learn stuff on Tuesday (proactive interference); what you learn on Tuesday makes it harder to remember what you learned on Monday (retroactive interference). To anyone familiar with these experiments, my discovery has a simple “explanation”: spatial interference. 3. Evolutionary plausibility. The study of printed materials (e.g., books) is so recent it is hard to imagine our brain has evolved to make it easy. In contrast, thousands and millions of years ago we had to learn about things in different places. Learning about food and danger in different places was especially important. When language arrived, the necessary learning (at first, attaching names to objects) is quite similar to my learning because the named objects were in different places. The study of vitamins and to some extent my work (especially the power of morning faces) show how hard it can be to figure out what we need for our brains and bodies to work well. How non-intuitive the answers may be.

These results suggest a new mnemonic device: Stand in front of an empty wall and imagine on the wall the associations you want to learn, each association in a different place like flashcards. This is a fast way of putting each association in a different place.

No More Antixoxidants

This fascinating blog post by Josh Mittledorf points out that antioxidants, once believed to reduce aging by reducing oxidative damage, have turned out to have the opposite effect. By reducing a hormetic effect, they make things worse. I’m a friend of Bruce Ames, one of main proponents of the free radical theory of aging. I’ve heard him talk about it a dozen times. The turning point — the beginning of the realization that this might be wrong — was this 1994 study, which found that beta-carotene, a potent antioxidant, increased mortality. Bruce did not have a good explanation for the counter-theoretical result. However, Mittledorf doesn’t mention an important fact which doesn’t fit his picture. Selenium, a potent antioxidant, also powerfully reduces cancer. Don’t stop taking selenium.

I also like this theoretical paper by Mittledorf about why aging evolved (turning off certain genes reduces aging) and how its evolution — not easily explained by conventional evolutionary ideas — is part of a range of phenomena that the conventional ideas cannot explain. One reason, maybe the main reason, that aging is adaptive is very Jane Jacobsian: it makes the community more flexible. Less likely to repeat old ways of doing things.

Thanks to Ashish Mukarji.

How I Read

In a review of a book by Alice Munro, Charles McGrath, who edited her at The New Yorker, wrote:

Many of these stories are told in Munro’s now familiar and much remarked on style, in which chronology is upended and the narrative is apt to begin at the end and end in the middle. She has said that she personally prefers to read stories that way, dipping in at random instead of following along sequentially,

That’s what I do. Most books I find are improved if I start in the middle and hop around. Doing so adds difficulty and mystery, which otherwise they are deficient in. Same reason I usually like reality shows more than scripted shows, scripted shows lack that attractive raw edge. Spy magazine had an article about writing guidelines for a woman’s magazine. The guidelines said start in the middle: Talk about someone (“he” this, “he” that) before identifying them.

A few great writers (Vladimir Nabokov, Jane Jacobs, Tolstoy) I don’t do this with. Some true crime (The Stranger Beside Me by Ann Rule) I don’t do it with. But most books benefit.

Flaxseed Lowers Blood Pressure

A new study found that ground flaxseed powerfully lowers blood pressure:

A patient population with peripheral artery disease (PAD) was selected as ideal to benefit from dietary flaxseed. . . . Patients received 30g of milled flaxseed (or placebo) each day over 6 months. [I eat 50 g/day — Seth] . . . No significant adverse events were associated with flaxseed ingestion. . . . SBP in the placebo group increased by ~3 mmHg and DBP remained the same over the experimental period. However, SBP levels were ~10 mmHg lower (P<0.04) and DBP was ~8 mmHg lower (P<0.004) in the flax group compared to placebo. In the flaxseed group, patients with a SBP <140 mmHg at baseline did not receive an anti-hypertensive effect but patients who entered the trial with a SBP > 140 mmHg at baseline obtained a sustained and significant 15 and 7 mmHg reduction in SBP and DBP, respectively, during the six months. . . . one of the most potent anti-hypertensive effects ever observed by a dietary intervention.

This supports my belief that we can improve our overall health by trying to improve our brains (which are more sensitive than the rest of the body). I have blogged about flaxseed oil many times. I became interested in it when I noticed it improved my balance. Balance measurements showed that the optimal dose (2-4 T/day) was higher than flaxseed oil manufacturers suggested. Then I and others noticed that taking this amount of flaxseed oil produced big improvements in gum health. Tyler Cowen, for example, no longer needed gum surgery. Go home, said the surgeon.

Thanks to Grace Liu.

Taobao’s Double Eleven: World’s Biggest eHoliday

Do the heads of eBay and Amazon know about the Chinese shopping site Taobao (like eBay without auctions)? If so, why don’t they imitate it? Maybe they can’t match its bigger selection (e.g., food, detergent) and better prices, but they could imitate the better seller feedback and instant communication (chat boxes) with sellers.

In my theory of human evolution I propose that we have ceremonies, rituals, and festivals (and associated holidays) because they caused trading that would otherwise not have taken place. Ceremonies and so forth increased the demand for certain goods — gifts and high-end clothes, for example. These goods are important economically far out of proportion to their volume or monetary value or daily use because they increase innovation. They help the most skilled artisans– the ones most likely to innovate — make a living.

The leaders of Taobao understand this function of festivals/holiday and have put it to use: They have created new festivals/holidays. The biggest is Double Eleven (November 11), which started five years ago. On Double Eleven, a large fraction of taobao merchants have discounts, big (50%) and small (5%). Sales have grown each year and this year reached about $3 billion, according to one site. According to a Chinese friend, the sales were about $10 billion. CyberMonday (about $1 billion in 2011) is far behind

I have never read about this function of ceremonies, festivals, etc., in any economics book or paper. Double Eleven shows their economic force. This neglect is an example of what I consider the biggest problem with modern economics: lack of attention to and lack of understanding of innovation.

Assorted Links

- Olive oil and the Willat Effect. “You can read about great olive oils, and their vast superiority over bad oils, all you want. . . . But until you try first-rate olive oil for yourself – actually put the good stuff in your mouth, and compare that experience to the bad stuff you’ve eaten in the past – you won’t really get it. . . . . Once you taste fine olive oils and their low-class imitations [side by side], though, you start to care.”

- Petraeus Affair: The journalism of what we don’t know.

- Tucker Max on book publishing. Disruptive innovation for popular authors.

- Animal self-medication. Sick animals eat differently than healthy animals.

Thanks to Alex Blackwood.

Bayesian Shangri-La Diet

In July, a Cambridge UK programmer named John Aspden wanted to lose weight. He had already lost weight via a low-carb (no potatoes, rice, bread, pasta, fruit juice) diet. That was no longer an option. He came across the Shangri-La Diet. It seemed crazy but people he respected took it seriously so he tried it. It worked. His waist shrank by four belt notches in four months. With no deprivation at all.

Before he started, he estimated the odds (i.e., his belief) of three different outcomes predicted by three different theories. What would happen if he drank 300 calories (2 tablespoons) per day of unflavored olive oil (Sainsbury’s Mild Olive Oil)? Aspden considered the predictions of three theories.

I called my three ideas of what would happen [= three theories that make different predictions] if I started eating extra oil Willpower, Helplessness and Shangri-La. (1) Willpower (W) is the conventional wisdom. If you eat an extra 300 calories a day you should get fatter. This was the almost unanimous prediction of my friends. Your appetite shouldn’t be affected. (2) Helplessness (H) was my own best guess. If you eat more, it will reduce your appetite and so you’ll eat less at other times to compensate, and so your weight won’t move. Whether this appetite loss would be consciously noticeable I couldn’t guess. This was my own best guess. (3) Shangri-La (S) is your theory. The oil will drop the set point for some reason, and as a result, you should see a very noticeable loss of appetite.

More about these theories. His original estimate of the likelihood of each prediction being true: W 39%, H 60%, S 1%. He added later, “I think I was being generous with the 1%”. After the prediction of the S theory turned out to be true, the S theory became 50 times more plausible, Aspden decided.

I like this a lot. Partly because of the quantification. If you were a high jumper in a world without exact measurement, people could only say stuff like “you jumped very high.” It would be more satisfying to have a more precise metric of accomplishment. It is a scientist’s dream of making an unlikely prediction that turns out to be true. The more unlikely, the more progress you have made. Here is quantification of what I accomplished. Although Aspden could find dozens of online reports that following the diet caused weight loss, he still believed that outcome very unlikely. Given that (a) the obesity epidemic has lasted 30-odd years and (b) people hate being fat, you might think that conventional wisdom about weight control should be assigned a very low probability of being correct.

I also like this because it is the essence of science: choosing between theories (including no theory) based on predictions. The more unlikely the outcome, the more you learn. You’d never know this from 99.99% of scientific papers, which say nothing about how unlikely the actual outcome was a priori — at least, nothing numerical. I can’t say why this happens (why an incomplete inferential logic, centered on p values, remains standard), but it has the effect of making good work less distinguishable from poor work. Maybe within the next ten years, a wise journal editor will begin to require both sorts of logic (Bayesian and p value). You need both. In Aspden’s case, the p value — which would indicate the clarity of the belt-tightening — was surely very large. This helped Aspden focus on the Bayesian aspect — the change in belief. This example shows how much you lose by ignoring the Bayesian aspect, as practically all papers do. In this case, you lose a lot. Anyone paying attention understands that the conventional wisdom about weight control must be wrong. Here is guidance towards a better theory. If not mine, you at least want a theory that predicts this result.