A new BBC series Metalworks! is about the history of British metal working. My theory of human evolution says that decoration — more precisely, our enjoyment of it — evolved because it helped the most skilled craftsmen make a living. Long ago, technology evolved via massive amounts of trial and error, which required subsidy since payoff (discovery with practical value) was so infrequent. It was much easier to discover/learn how to make something that looked better than something that worked better, but the two sorts of discoveries were correlated: trial and error produces both.

The episode on ironwork (The Blacksmith’s Tale) makes explicit how desire for decoration made it easier for the most skilled iron workers to make a living:

[Expert, at 16:50:] “I think decoration entirely depends on the amount of money the patron wanted to spend on that particular object.” [Narrator:] By the end of the 15th Century, wealthy patrons, such as the Church and monarchy, were hand-picking known craftsmen at the top of their game to match a commission’s requirements. When King Edward IV commissioned the Cornish smith John Tresillion to make these Gothic gates at Windsor in 1497, he did so with good reason. . . . [Expert:] “No blacksmith, ordinary blacksmith who was used to making horseshoes, could dream of working to this standard of perfection.”

Quality of decoration is easy to see. It doesn’t matter but it correlates with something that does matter — amount of trial and error (more trial and error, more innovation). We reward decoration to increase innovation.

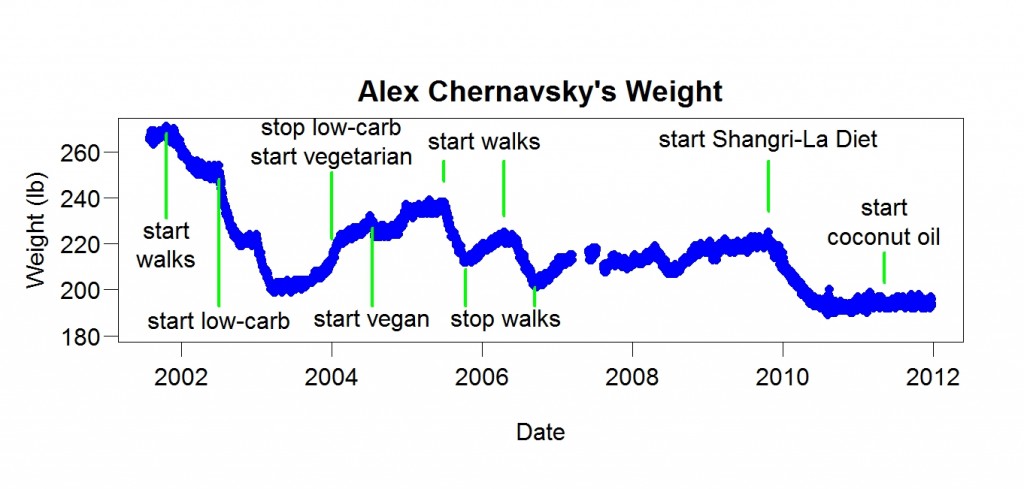

The Shangri-La Diet derives from a theory of weight control that emphasizes smell-calorie learning. Smell-calorie learning evolved for the same logical reason. Smells don’t actually matter for health. But they are easy to notice and they correlate with things that do matter for health, such as calories. Via smell-calorie learning we learn the correlations. After that the foods that smell best are the ones that contain more calories.